An independent commission is racing to redraw Detroit’s voting maps under a federal court order − but the change may not elect more Black candidates

Marjorie Sarbaugh-Thompson, Wayne State University and Lyke Thompson, Wayne State University

A panel of three federal judges ruled on Dec. 21, 2023, that a few state House and Senate legislative maps drawn by an independent Michigan commission violate the Voting Rights Act. Their ruling, which is currently under appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, says the maps dilute Black voting power in 13 Detroit area legislative districts and those districts must be redrawn.

The Conversation interviewed Marjorie Sarbaugh-Thompson and Lyke Thompson, professors of political science at Wayne State University who have written about the redistricting commission.

Can you tell us about the commission?

The Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission was created by a statewide ballot initiative to purge partisan politics from redistricting. The initiative passed in 2018 with 61% support. The commissioners are citizen volunteers drawn randomly from three pools of applicants: four Democrats, four Republicans and five nonpartisans. Our research found that Michigan’s commission has more members not affiliated with a political party than any other state redistricting commission.

The commission created 2022 district maps for Michigan’s U.S. House, state House and state Senate elections that were fair to both major political parties, according to PlanScore, a consortium of legal, political science and mapping technology experts.

How were Michigan legislative maps drawn before the commission?

Michigan’s 2010 district maps were drawn by Republican politicians and have been held up as examples of extreme partisan gerrymandering.

These lopsided maps triggered a movement, Voters Not Politicians. Volunteers collected 425,000 signatures to get a constitutional amendment on the Michigan ballot to take redistricting out of the hands of politicians.

How did the commission create the new maps?

The commission’s process was exceptionally transparent. It was required to hold at least 10 public meetings to gather input prior to drawing maps; it held 16. It had to hold at least five public meetings after publishing its first drafts; it held 38. Citizens made more than 25,000 public comments at meetings or in written form.

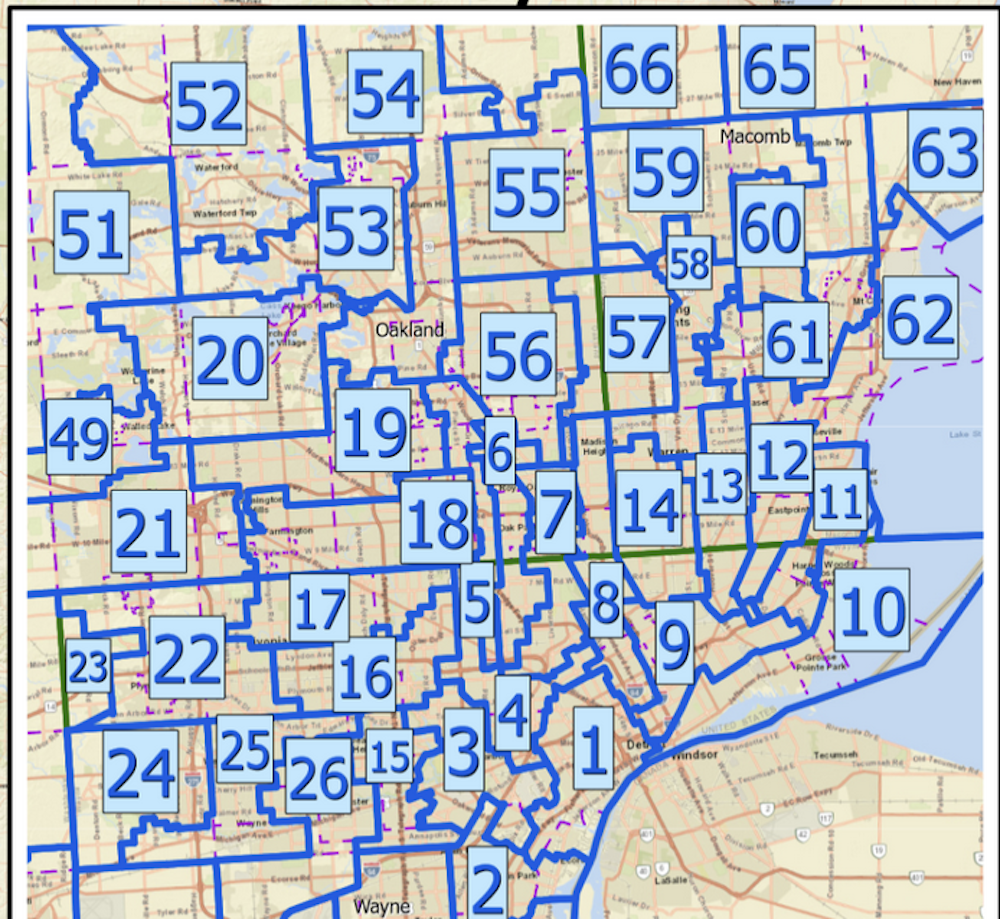

The commission’s maps drawn for the 2022 election cycle did eliminate some majority Black districts in both the state Senate and House, but they more accurately reflected Michigan voters’ preferences for Republican and Democratic candidates. That year, Democrats narrowly won control of both state legislative chambers for the first time since 1984, and the U.S. House delegation includes seven Democrats and six Republicans, an outcome that is consistent with total votes cast.

Why were the new maps challenged?

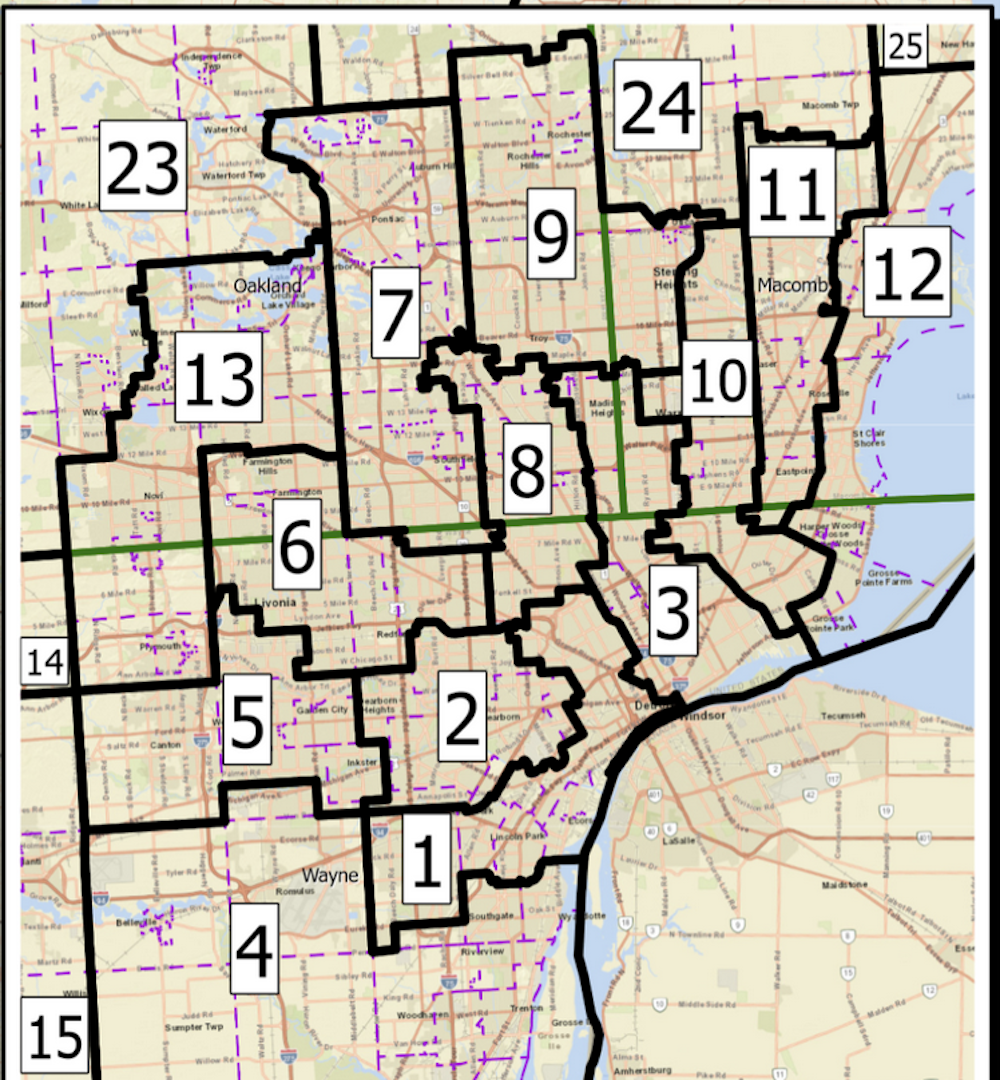

In 2022, a group of Detroit voters filed a lawsuit, Agee v. Benson, challenging a few districts based on the federal Voting Rights Act. A three-judge panel ruled that 13 districts in the Detroit metro area – seven for the state House and six for the state Senate – are unconstitutional because they violate the equal protection clause, which says district lines cannot be drawn based solely on race.

The commissioners appealed the ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. But on Jan. 22, the high court refused to stop the process of redrawing the maps. The panel now has until Feb. 2 to present redrawn maps for public comment, with final ones due in March. The Supreme Court may still rule on the commission’s appeal – but likely not until after the state’s primary elections on Aug. 6.

Why did Detroit lose majority Black districts?

Each new state House district is supposed to have 91,612 residents, a number derived from dividing Michigan’s 2020 population by its 110 state House districts. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Detroit lost 93,361 Black residents over the past decade, while losing only 74,666 people in total, reflecting an influx of White, Latino, multiracial and Asian residents.

One way the commission adjusted for these population shifts and provided opportunities for Black candidates was to create districts that stretched across municipal boundaries – from Detroit into Macomb and Oakland counties. These new district boundaries combined Black voters in the suburbs and Detroit, creating a large enough percentage to allow minority candidates to win elections.

The decline in majority Black districts in Detroit isn’t unique to the 2022 district maps. In 2012, the Michigan Legislative Black Caucus protested losing two other Detroit state House districts. Those losses were related to the drop in Detroit’s 2000-2010 population. In other words, the declining Black population in Detroit is a persistent demographic trend that complicates applying the Voting Rights Act.

Why is it so complex to make the Voting Rights Act work in Detroit?

Under the Voting Rights Act, maps can neither crack nor pack minority voters.

Cracking is when minority voters are spread across multiple districts, which makes it harder for them to win elections.

Packing groups more minority voters than are typically needed in a district to elect a minority candidate and also dilutes the number of minorities likely to be elected overall.

Election results demonstrate that in Southeast Michigan general election contests, many Michigan voters care more about whether a candidate is a Democrat or a Republican than their race. Experts hired by the commission advised them that 35% to 45% is the sweet spot between packing and cracking Black voters in these districts. The seven House districts ordered redrawn by the court have 37% to 49% Black voters.

Black migration from Detroit to its inner-ring suburbs provided the commission a way to unpack majority-minority districts and avoid cracking Black suburban populations. For example, the Black population of Eastpointe, a suburb immediately north of Detroit in Macomb County, increased from 29% in 2010 to 52% in 2020.

Black candidates won 2022 elections in five of the seven House districts that the court has ordered redrawn. But the plaintiffs in Agee v. Benson argue that it takes higher percentages of Black voters to win primaries because so many candidates run and end up splitting the vote. In two primary elections where Black candidates lost, the votes were split. In District 11, which is 44% Black voters, the ballot had nine candidates. Veronica Paiz, a Hispanic woman, won with less than 19% of the votes cast. In District 8, which has 46% Black voters, Mike McFall, a white man, won the primary with 38% of the vote against two Black candidates.

So you’re suggesting too many primary candidates, not map boundaries, dilute the Black vote?

Yes, that is what the evidence suggests. For example, three Black primary candidates lost in the 9th House District, which has 53% Black voters. The 5th House District with 57% Black voters attracted five primary candidates; a white woman won with 38% of the votes cast, while two Black men won 40% of the primary votes between the two of them. So changing district boundaries isn’t an effective way to solve the problem.

Other solutions like ranked choice voting could increase opportunities for Black primary victories, regardless of how many candidates run. This voting system is gaining popularity in places as disparate as Alaska, Maine and New York City.

The new maps must be finalized by March 29. What does this mean for 2024 elections?

Given the tight deadline for the commission to publish the maps, receive public comments and then vote on the maps, candidates will have a shorter window to organize primary election campaigns. Some incumbents will see their constituents shift again. And it is possible that Black voters will be packed into a smaller number of districts.![]()

Marjorie Sarbaugh-Thompson, professor of political science, Wayne State University and Lyke Thompson, professor of political science, Wayne State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.