From cancer to AIDS back to cancer and perhaps beyond

Eduardo Palomino has accomplished a lot over his career as cancer researcher and lecturer in the Department of Biological Sciences and director of research and natural products at the Walker Cancer Research Institute, which is housed at WSU. His emphasis has been on cancer research, including recent discoveries about how common household materials can help fight cancer. One of the initial highlights of his career, however, came when he was a postdoctoral researcher at WSU and centered on a major breakthrough: the discovery of the first drug to offer any real hope in treating people with AIDS. That drug is called azidothymidine or AZT.

The story begins in the 1960s when WSU School of Medicine and Michigan Cancer Foundation researcher Jerome Horwitz synthesized AZT as a potential cancer treatment. It didn’t work against cancer, so he shelved it and moved on to other treatment candidates. Nearly two decades later, AIDS reared its head and once the causative virus —HIV — was identified in 1984, a massive hunt ensued to find something to counter it. The large pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome took up the gauntlet and in 1987 announced it had discovered a compound that suppressed HIV by preventing it from self-replicating. That compound was AZT and before long, the spotlight swung to Horwitz’s lab.

By then, Palomino was in his third year as part of the lab. "It was exciting to be there when that happened!" he recalled. "Once we learned about AZT affecting HIV, I started designing additional materials that could potentially work more effectively, but nothing matched the capability of AZT," he recalled. "And even today, AZT remains an important part of AIDS treatment and prevention."

Cancer discoveries

Palomino soon put his full effort back into cancer research and by 1990, he was running his own research lab while continuing to collaborate with Horwitz. Palomino recounts, "We set out to find new compounds to fight cancer. That involved making the compounds and working with another group that had a novel method to test the material in vitro and in vivo (in cell culture and inside living organisms)" As a result, they were able to use this highly accurate system to identify several compounds that had anti-cancer activity and they sold one to the large pharmaceutical company Sanofi. Remarkably, he said, WSU received $2 million from that sale and named the compound its "invention of the year" in 2002. Unfortunately, he noted, "the drug didn’t pass the first stage of clinical trials, so Sanofi ultimately dropped it."

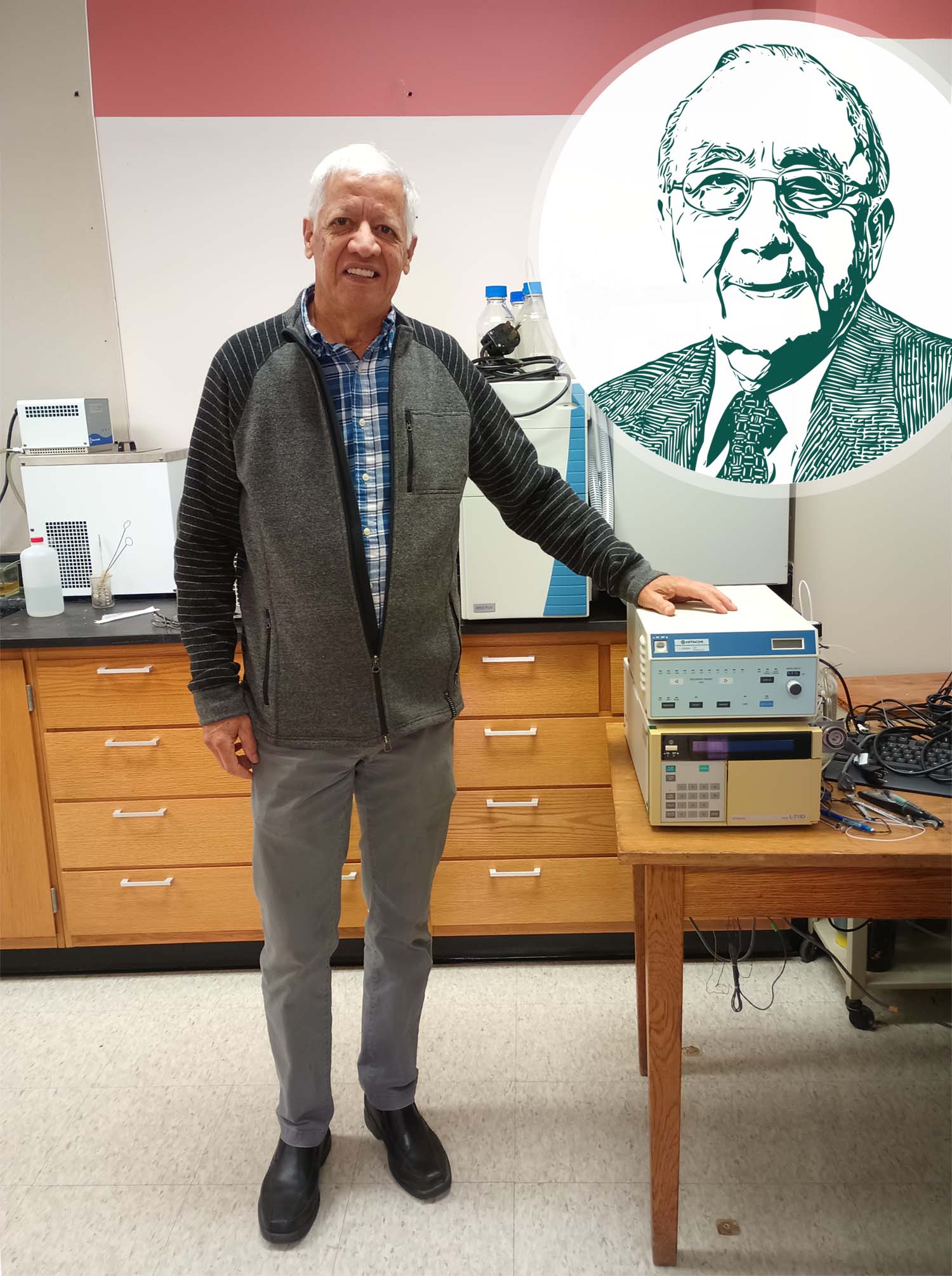

Palomino and Horwitz went on working together until Horwitz retired in 2007. Following Horwitz’s death in 2012 (at the age of 93), Palomino inherited his lab equipment, which he still uses in his lab today, documenting the closeness to his former famous mentor.

Palomino’s focus evolved over the years toward his current area of study: designing anti-cancer materials that are activated by other molecules at the target site. Such materials are called prodrugs. Specifically, he became interested in prodrugs that are activated by molecules known as hydroxyl radicals. "Cancer cells produce hydroxyl radicals to destroy the surrounding normal cells, which allows the cancer to grow more," he explained. "So the idea is to develop a prodrug that can be delivered and activated only in the presence of hydroxyl radicals, so only at the cancer site." In this way, he said, the prodrug would bypass healthy cells elsewhere in the body and therefore avoid the side effects common to systemic chemotherapies that damage healthy cells along with cancerous cells.

Jumping hurdles

The notion of cancer-targeted prodrugs was sound, but it had one big drawback. "In order to test them, I needed a commercial source of hydroxyl radicals, but I found there was none," he said. He pored through the scientific literature and learned that a combination of bleach and hydrogen peroxide would yield hydroxyl radicals and then modified that reaction by replacing bleach, which can be toxic to human tissue, with one of its key components: hypochlorous acid. The body naturally makes hypochlorous acid as part of its immune response to battle infection. Palomino found no commercial source for hypochlorous acid either, so he figured out how to make that as well. "It took me a while, but in the past two years, I have been successful in isolating and purifying hypochlorous acid and I have several patents for those processes," he said.

Beyond that, he has found another target for prodrugs because cancer cells produce hypochlorous acid, too. "So I now have a way to activate anti-cancer prodrugs in the presence of either hydroxyl radicals or hypochlorous acid and that is what I’m working on," he said. At the same time, he is exploring the use of a salt ion called ferrocyanide to generate hydroxyl radicals. He also obtained patents for those processes.

In addition to that work, Palomino envisions uses for hypochlorous acid and hydroxyl radicals that extend beyond cancer prodrugs. "Right now, for instance, I’m trying to develop a good method to produce hydroxyl radicals that people can inhale. That could lead to an inhaler activated to produce hydroxyl radicals as a way to treat bacterial and viral infections, including the common cold," he said.

Overall, he remarked, "The main takeaway from this work is that we have disease solutions right in front of us, but they haven’t been put to use yet." He added, "That’s why I am publishing my results: to show how these common materials — hydrogen peroxide and bleach — should not just be considered household cleaners, but also be seen as having potentially important roles in fighting cancer and a number of other diseases."